Why Bhutan’s tilt towards China may ‘significantly change’ regional dynamics

- Negotiations on border dispute and diplomatic ties moved forward when top diplomat visited Beijing

- Small Himalayan kingdom is sandwiched between two Asian giants competing for influence

At the heart of border negotiations between Beijing and Thimphu, which began in 1984, is the disputed tri-junction on the Doklam plateau between China, Bhutan and India – where Chinese and Indian troops had a tense 73-day stand-off in 2017.

Negotiations on the border dispute and diplomatic relations reportedly made progress during Bhutanese Foreign Minister Tandi Dorji’s visit to Beijing, the latest sign that China’s ties with one of India’s closest allies are warming, according to observers.

They said that settling the border issue – aside from raising concern in New Delhi about Bhutan’s tilt towards Beijing and China’s inroads into South Asia – could have implications for regional geopolitics, and the international system.

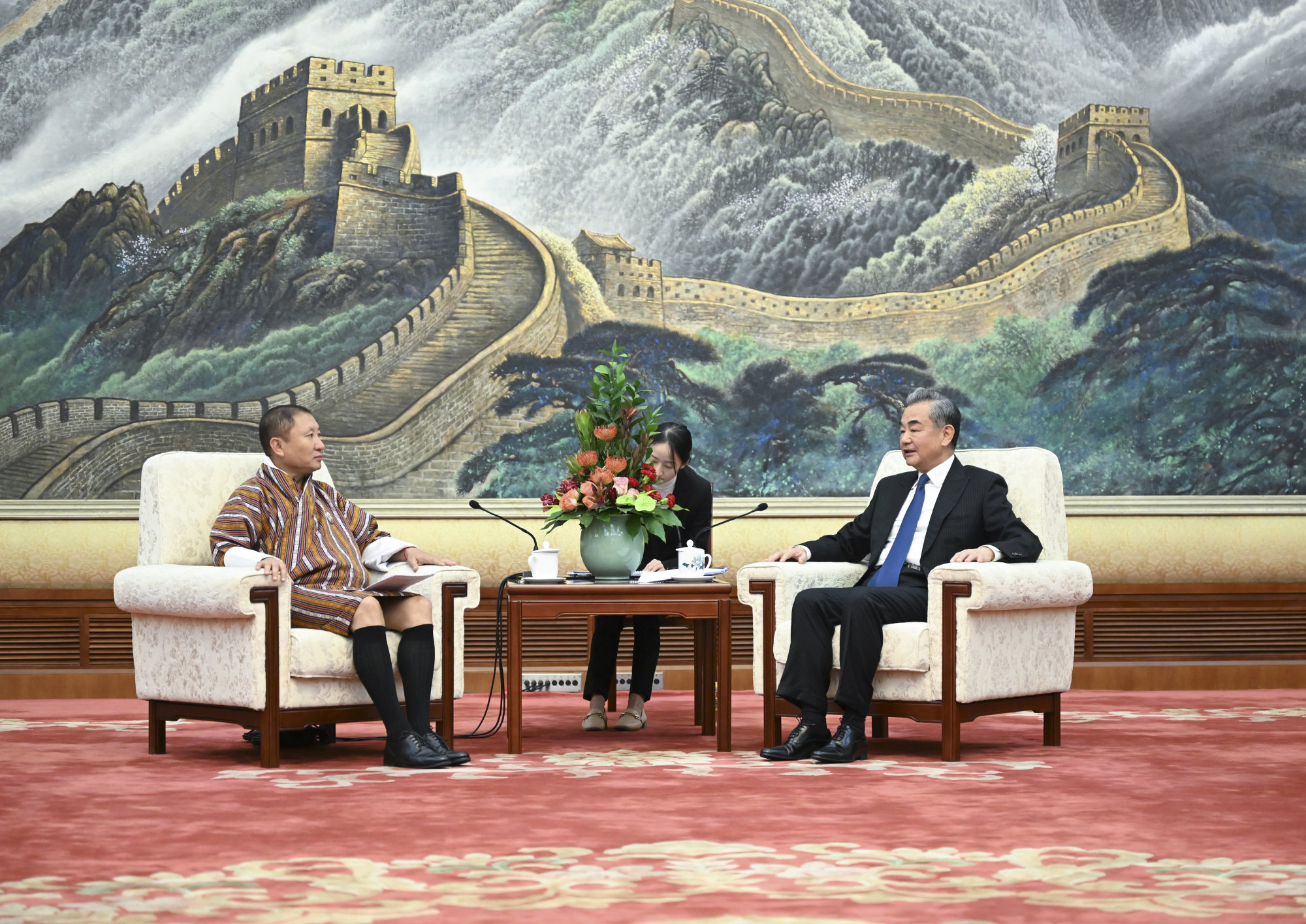

Dorji appeared to get a warm reception last week when he visited Beijing for the first official boundary talks in seven years. He met Vice-President Han Zheng and Foreign Minister Wang Yi and was given a tour of historical landmarks in the capital, according to China’s foreign ministry.

In what Chinese experts called “a breakthrough”, the two sides signed a cooperation agreement on the responsibility and functions of a technical team for the delimitation and demarcation of the boundary and agreed to “build on the positive momentum”.

The official Xinhua news agency said both sides agreed to accelerate the demarcation process and the establishment of diplomatic relations.

“The two sides should seize historical opportunities, complete the important process as soon as possible, and designate and develop the friendly relations between the two countries in legal form,” Wang told Dorji on Monday.

In response, Dorji was quoted by Xinhua as saying that Bhutan was “willing to work with China to strive for an early settlement of the boundary question and advance the political process of establishing diplomatic ties”.

Robert Barnett, founder and former director of Columbia University’s modern Tibetan studies programme, said Dorji’s visit and recent remarks by the Bhutanese prime minister could indicate a major shift in the country’s foreign policy.

“What China seems to want next is an embassy in Thimphu, which would significantly change the dynamics of diplomacy in the region. And it does seem as if [Thimphu] is strongly hinting that it is inclined to grant this demand,” he said.

It would also be a big shift in Bhutan’s long history of avoiding big-power politics, given its policy against diplomatic ties with the five permanent members of the UN Security Council, including China, according to Barnett.

“If it lets China in, it would have to let the other [four] governments have embassies as well. It seems very unlikely that India would welcome such a dramatic increase in China’s presence in Bhutan – but it’s even more unlikely that Bhutan has not already received support from India for its plans,” he said.

Bhutanese Prime Minister Lotay Tshering said in an interview with The Hindu newspaper earlier this month: “Theoretically, how can Bhutan not have any bilateral relations with China? The question is when, and in what manner.”

According to Tshering, the road map included first agreeing to the demarcation of the border in talks on the table, and then a joint visit to the sites along the demarcated line on the ground, before finally and formally demarcating the boundary between them.

The Bhutanese leader, who is viewed as a China-friendly figure, also told the newspaper that a possible land swap plan involving the Bhutan-controlled Doklam area was among proposals discussed during border talks with Beijing.

China-India border talks: dispute to be resolved ‘as soon as possible’

New Delhi is particularly sensitive about the strategically important Doklam plateau due to its proximity to the Siliguri Corridor, or the “Chicken’s Neck”, that connects to India’s northeastern states.

In an editorial on Thursday, The Hindu listed the fate of Doklam as one of India’s two red lines on Bhutan’s ties with China. “A second line will likely involve Thimphu going slow on normalising ties and opening itself up to a permanent Chinese diplomatic presence, while continuing with border talks,” it said.

The newspaper said New Delhi “has been very wary” about the possibility of a border settlement and formal diplomatic ties between Beijing and Thimphu, both of which “increasingly appear inevitable”.

The Doklam issue was clearly front and centre in last week’s border talks, according to Shashi Asthana, a retired Indian major general and chief instructor at the United Service Institution of India think tank in Delhi.

He said the small Himalayan kingdom was not an economically attractive destination for China given its limited resources.

“China’s outreach to Bhutan, therefore, has the strategic intention of somehow convincing or luring Bhutan to get the Doklam plateau … and extend its reach towards Siliguri Corridor to increase Indian concerns,” he said. “To that extent, it may not be wrong to deduce that Beijing’s efforts to pull Bhutan closer could partly be aimed at New Delhi.”

Jagannath Panda, head of the Stockholm Centre for South Asian and Indo-Pacific Affairs at the Institute for Security and Development Policy in Sweden, also said China’s move towards establishing diplomatic ties with Bhutan was aimed at reducing India’s influence among its South Asian neighbours.

He said China had, since the 1990s, offered to exchange territory in central Bhutan for Doklam in a “package deal”. And while India’s ties with Bhutan had been a strategic barrier for China in the past, it was becoming increasingly difficult for Thimphu to maintain its neutral stance.

“Traditional ties have not brought about sufficiently close bilateral coordination on strategic issues – an area of concern for India amid the current geopolitical volatility,” he said.

Panda said if a diplomatic agreement was reached between China and Bhutan it could change the status quo in the tri-junction area of India-Bhutan-China, particularly in the Doklam valley, where it could be advantageous for the Chinese military.

“India must have a serious and pointed discussion with Bhutan on how not to allow China to have a bilateral accord on the boundary dispute to firm diplomatic ties,” he said. “New Delhi can’t afford to lose Bhutan as a reliable neighbour in South Asia and, importantly, as a reliable security partner in the Himalayas.”

But Yun Sun, co-director of the East Asia programme and director of the China programme at the Washington-based Stimson Centre, said it was unlikely Bhutan would negotiate its border with China without Indian involvement.

“And in the tri-junction area, it will require the three parties’ consent for any deal to be reached. So if a deal is shaping up, India must be involved. If the border is settled, there is no fundamental obstacle to the diplomatic normalisation between China and Bhutan,” she said.

“If a deal is reached, it would imply the resolution of some portion of the disputes between China and India, and the removal of one irritant. As China-India relations have been in stalemate since 2020, if a deal is reached on the Bhutan-China border, I will see it as a positive development,” Sun added.

Wang Dehua, a regional affairs expert at the Shanghai Municipal Centre for International Studies, said China was also concerned about Bhutan’s ability to make its own decisions under India’s influence.

Under a 1949 bilateral treaty, Bhutan was bound by India’s guidance in regard to its external relations. Although that provision was removed in a revised 2017 treaty, Wang said it was far from certain that the pledges by Bhutanese officials could be honoured and delivered.

He noted that China viewed Doklam as a bilateral issue between Beijing and Thimphu in which New Delhi should not have been involved.

“It is highly unlikely that China would make key concessions on Doklam. Unfortunately, India appears to be even more sensitive towards Doklam because it tends to see it as part of lessons learned from the defeat in the 1962 India-China war, which underlined the importance of Bhutan and the Siliguri Corridor in particular,” Wang said.

Zhao Gancheng, a researcher with the Shanghai Institutes for International Studies, noted that Beijing released a policy paper on Tuesday stressing the importance of its neighborhood diplomacy, coinciding with Dorji’s visit.

It mentioned the issue of border demarcation and the need to resolve issues with 12 out of 14 land neighbours.

“If the China-Bhutan border is demarcated first, it won’t be too long before they set up diplomatic relations. But if they establish diplomatic relations first, it will be hard to predict how long it will take to complete border demarcation given its sensitivity and complexity,” he said.

‘Difficult to agree’: China-India border row spills over into water resources

Asthana also cast doubt on an imminent border settlement. “I am not very optimistic about the success of delimitation leading to demarcation, with nothing much moving on ground beyond exchange of maps of some areas. Bhutan understands the sensitivities of India pertaining to the area of tri-junction,” he said.

He noted that Tshering and Dorji said early this year that no border agreement would be made “against India’s interests” and clarified that any talks about the tri-junction at Doklam would only be held trilaterally between India, Bhutan and China.

Barnett pointed out that Tshering did not make it clear if the land exchange deal being discussed with China would include Doklam.

“He didn’t deny it, but he only said it was being discussed. What we are more likely to see is that the exchange will involve Bhutan giving up land just to the north of Doklam – land which China has already seized and partly settled – in exchange for China giving up some of the land it has seized in the north,” he said.

But he nonetheless expressed concern about the implications of such a deal.

“If Bhutan agrees to any form of land swap with China, whether it includes Doklam or not, this will have seismic implications for the international system,” he said.

“It will give China total impunity for what was an unquestioned abrogation by Beijing of its treaty commitments to Bhutan – which included an obligation not to change unilaterally the status of disputed territory – and it will reward China unreservedly for the seizure and occupation of what is customarily recognised as another country’s land,” he said.

“It suggests that China could make a claim on any territory it wants that is held by a weaker neighbour, however dubious or new that claim is, and then settle that land and force a smaller country to give it up.”