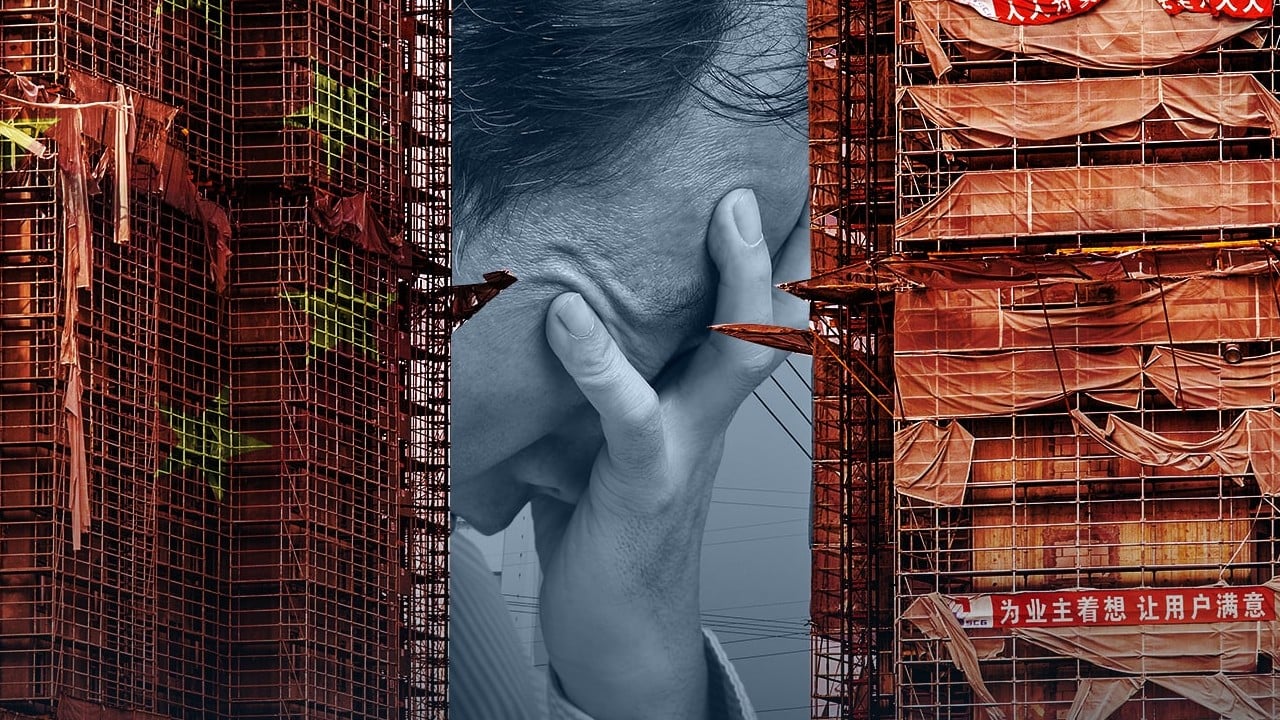

Wall Street snubs China for India in a historic markets shift

- Over the past two decades, India’s gross domestic product and market capitalisation rose in tandem from US$500 billion to US$3.5 trillion

- India briefly overtook Hong Kong as the fourth-largest equity market last month; Morgan Stanley predicts it will be the world’s third-biggest by 2030

“People are interested in India for several reasons, one is simply it’s not China,” said Vikas Pershad, Asian equities portfolio manager at M&G Investments in Singapore. “There’s a genuine long-term growth story here.”

While the bullish sentiment about India isn’t new, investors are more likely now to see a market that resembles the China of times past: a vast, dynamic economy that is opening up to global money in novel ways. Nobody expects a smooth ride. The country’s population is still largely poor, stock markets are expensive and bond markets insular. But most are making the crossover anyway, calculating that the risks of betting against India are greater.

History shows that India’s economic growth and the value of its stock market are closely linked. If the nation continues to expand at 7 per cent, the market size can be expected to grow on average by at least that rate. Over the past two decades, gross domestic product and market capitalisation rose in tandem from US$500 billion to US$3.5 trillion.

China’s timid stimulus hurts stocks as funds flee to India, Japan, US assets

Capital flows reflect the enthusiasm. In the US exchange-traded fund market, the main fund buying Indian stocks received record inflows in the final quarter of 2023, while the four largest China funds combined saw outflows of almost US$800 million. Active bond funds have put 50 cents to work in India for every dollar they pulled from China since 2022, according to EPFR data.

China intervenes in market as regulator steps up scrutiny of stock rout

Japan’s retail investors, who have traditionally favoured the US, are also warming up to the country. Five of their India-focused mutual funds now feature among the top 20 by inflows. Assets at the largest – Nomura Indian Stock Fund – are at a four-year high.

Hedge funds including Marshall Wace point to India’s strong growth and relative political stability as reasons to remain optimistic about consistent pockets of growth, even if the broader market still has expensive valuations.

Karma Capital, which manages money in India for institutions like Norges Bank, says US investors are especially eager to enter and learn more about the market. Rajnish Girdhar, the fund’s chief executive, recalled one client responding with unusual speed to several India queries.

“We would send something Friday and before we returned Monday morning, she’d have responded, which means she was working on the weekend,” he said.

India has capitalised on changing power dynamics with China, a decades-long rival. If China is viewed as a threat to the Western global order, India is regarded as a potential counterweight – a country increasingly equipped to assert itself as a viable manufacturing alternative to Beijing.

Nations like the US see the need to have strong business ties with India, even though they have criticised the country’s tax policies. India now accounts for more than 7 per cent of the iPhone’s global output and is pouring trillions of rupees into upgrading infrastructure.

These efforts are part of Modi’s plan to sell India as the world’s new growth engine. The government will boost infrastructure spending by 11 per cent to 11.1 trillion rupees (US$134 billion) in the coming fiscal year, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman said last week in her interim budget speech.

Chinese stocks fell US$5 trillion due to zero-Covid, benefiting India

“The investment cycle is picking up with public capital expenditure and infrastructure initiatives,” said Jitania Kandhari, deputy chief investment officer for solutions and multi-asset group at Morgan Stanley Investment Management.

India is also building a vast ecosystem of technologies aimed at pulling many more people into the digital marketplace. Alphabet’s Google Pay plans to work with India’s mobile-based payments system to expand services beyond the country.

“For the first time, you have hundreds of millions of Indians with a bank account and access to credit,” said Ashish Chugh, a money manager at Loomis Sayles. “This is bound to attract global companies to India, and with them global investors, too.”

Some hurdles do persist. Indian equities are among the most expensive in the world. The S&P BSE Sensex Index has almost tripled from its March 2020 low, while earnings have only about doubled. The gauge trades at more than 20 times future earnings, 27 per cent more expensive than the average during the 2010-2020 period.

Beijing’s recent attempts to support its markets have prompted some investors to contemplate a change in strategy. Global funds took out more than US$3.1 billion from Indian shares in January, the largest monthly outflow in a year, according to Bloomberg data.

“An enormous success is priced into India’s markets,” said Mark Williams, a fund manager at Somerset Capital Management. “The question is how much of that is not priced in. There’s certainly a risk that Indian markets can go sideways for some years.”

Investors are bracing for a correction after eight straight years of annual gains in local shares. Modi is expected to win a third term in office during this year’s national elections, especially after his party’s sweep of recent state polls signalled existing policy will continue. But a weakened ruling party could jolt markets in the short-run.

Modi’s social agenda, which his critics say favours the nation’s Hindu majority, also threatens stability in a country that has more than 200 million religious minorities. Turning India’s potential into an economic reality that benefits all citizens is tough, especially in a multilingual democracy with vast cultural differences between states.

“India still has a long way to go,” said Charles Robertson, head of macro strategy at FIM Partners. “Potential peak growth is still under what China did achieve.”

Even with those risks, India fans say they are investing for the long term. With a still-low per capita income, the country is setting the stage for multi-year expansion and new market opportunities, they said.

India’s once-insular financial markets will continue to open up. With foreign ownership just above 2 per cent, the nation’s US$1.2 trillion sovereign-bond market is being added to JPMorgan Chase’s global debt index from June. This may lure as much as US$100 billion of inflows in the coming years, HSBC Asset Management said.

Confidence in India stems from the long-term impact of such initiatives, not necessarily from the near-term outlook on the nation’s stocks and bonds, according to Gaurav Narain, a money manager who advises India Capital Growth Fund.

“There is no longer a need for a ‘sell the India story’ pitch from us,” he said. “It’s a ‘buy into India’ from people who are aware of the positive changes.”