The Nobel Prize must be decolonised to truly celebrate global excellence

- The US and the UK alone contribute about 55 per cent of Nobel laureates, underscoring the pervasiveness of Western intellectual culture

- A Eurocentric perspective contradicts not only the essence of science, but also the original intent of founder Alfred Nobel

As we stand on the brink of the Nobel Week events slated for December 6 to 12, it is worth noting that Nobel laureates, whether by affiliation or residence, overwhelmingly hail from the Western world. As affiliation is also a marker of regional origin, it spotlights the pervasive influence of Western research institutions and intellectual culture on the achievement and acknowledgement of excellence.

It is now time for the Nobel Prize to liberate itself from its deeply ingrained Western imperialist identity and metamorphose into a symbol that genuinely mirrors the diverse tapestry of intellectual contributions.

The historical roots of the Western dominance of the Nobel Prize can be tracked back to the science-imperialism nexus. Historian Odd Arne Westad has shed light on the symbiotic relationship between Western imperialism and advancements in military science and technology. His nuanced analysis suggests that since the late 18th century, the trajectory of Western dominance had been influenced profoundly by military innovations.

Westad’s exploration underscores the intricate connection between the strategic use of science and technology, and imperialistic pursuits. While not explicitly addressing the Nobel Prize, Westad’s perspective implies a broader context in which Western dominance extends beyond the geopolitical realm to encompass institutions such as the Nobel Prize.

Hong Kong must wrestle with Britain’s colonial legacy, not romanticise it

While criticism of the Nobel Prize has gained momentum, the point here is to delve into the significance of the data. The Nobel Prize stands at a critical juncture, necessitating a profound transformation.

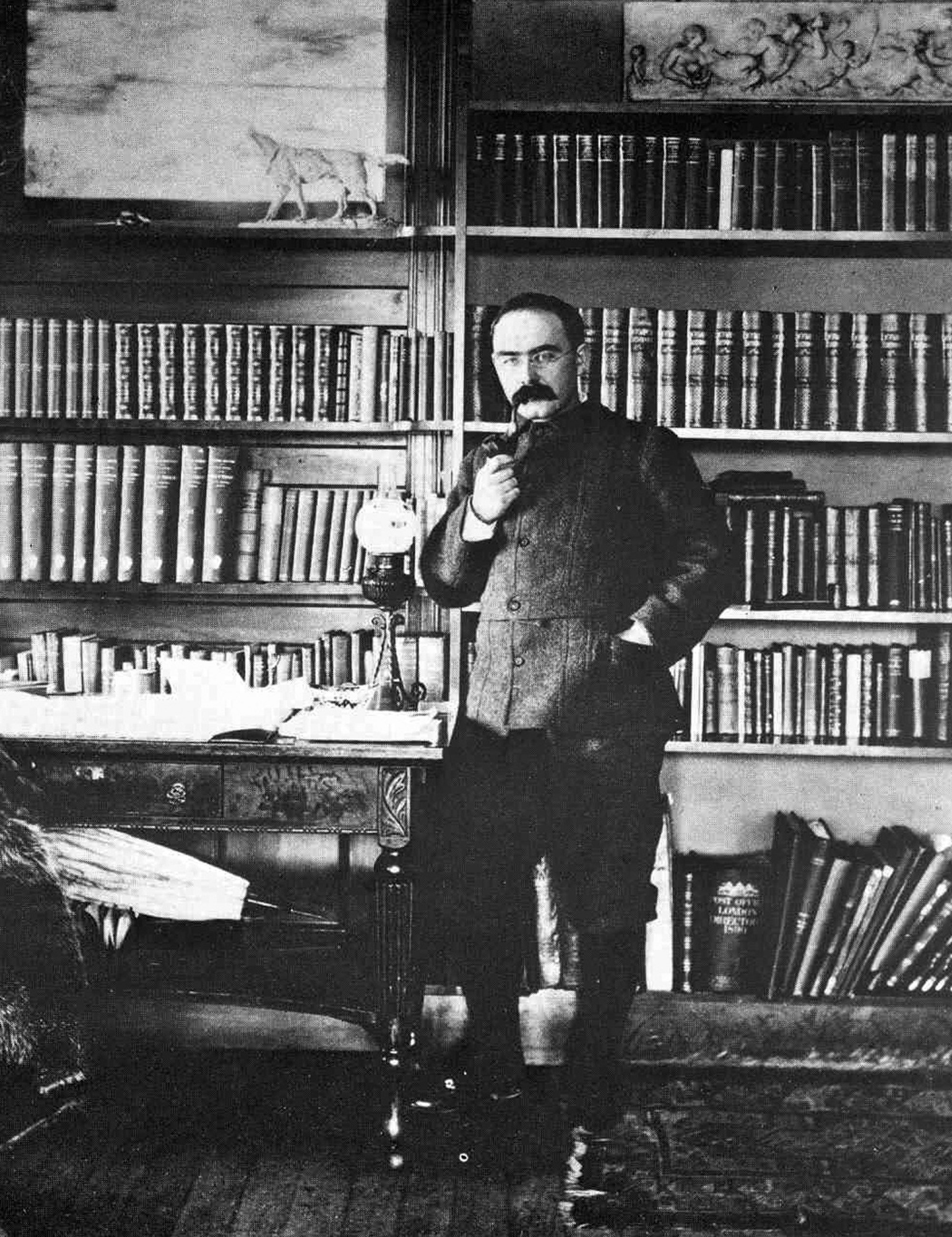

Nobel laureates like Rudyard Kipling openly championed white supremacy, echoing sentiments prevalent among European and American scientists in the 19th and 20th centuries. Notable figures such as German Nobel laureates Philipp Lenard and Johannes Stark supported Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich.

Moreover, Eurocentric assumptions have perpetuated a blindness to the potential brilliance of scientists beyond the confines of the WEIRD world – Western, educated, industrialised, rich and democratic. This narrow perspective contradicts the essence of science, which is the relentless pursuit of unbiased, universal knowledge. While Western science undeniably holds significance, it constitutes only a fraction of the vast, evolving body of human knowledge.

The repercussions extend to the marginalisation and exploitation of indigenous knowledge by Western imperialist science. Colonial conquests led to the suppression of indigenous knowledge systems, which were often disregarded unless they served Western interests. Only recently have Western institutions begun to recognise the value of indigenous science, which holds immense potential for addressing various global challenges.

In response, a global movement is gaining momentum, calling for the decolonisation of science. This movement aims to challenge white European supremacy and advocates for a more diverse, inclusive and relevant scientific landscape. While the call for decolonisation is not without challenges – risks include extremist and nationalistic responses – the movement offers an opportunity for careful and critical reflection, along with constructive communication.

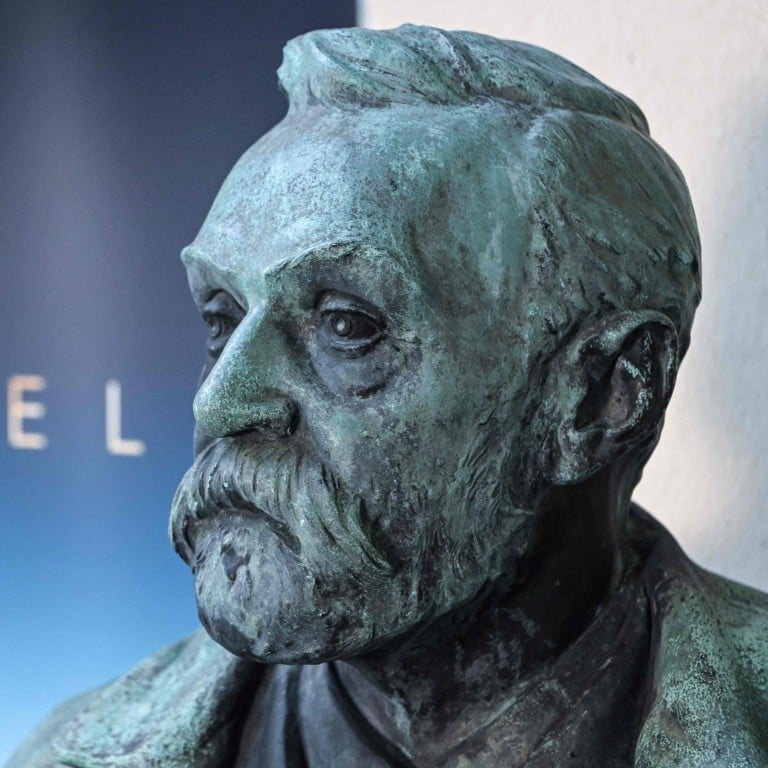

Considering these challenges, the Nobel Prize must realign itself with the original intent of its founder, Swedish inventor and industrialist Alfred Nobel: to benefit humanity.

The upcoming Nobel Prize ceremonies should transcend the mere conferring of accolades, instead serving as a platform for global intellectuals to dissect the enduring effects of Western imperialism on the prize, and chart a transformative course. In embracing a more inclusive identity, the Nobel Prize could genuinely symbolise scientific prowess in the service of the welfare of all people, irrespective of their geographic or cultural origins.

As we reflect on the evolving narrative of the Nobel Prize, it is important to consider the broader implications of Western dominance and the ensuing call for reform. This would resonate with contemporary conversations around diversity, inclusion and the ethical conduct of scientific research.

The clamour for change underscores not only the necessity of acknowledging past injustices but also the urgency of creating a scientific landscape that fosters collaboration, understanding and the mutual exchange of knowledge. By embracing a more comprehensive approach, the Nobel Prize can become a catalyst for a global intellectual renaissance that celebrates the richness of diverse perspectives.

The Nobel Prize stands at a crossroads: it could persist as a relic of Western imperialist dominance or transform into a beacon of global intellectual achievement. Decolonising the Nobel Prize is not just an idealistic aspiration; it is an imperative step to honour Alfred Nobel’s legacy and ensure that the pursuit of knowledge benefits the entire human race.

May the prize evolve into the most sought-after accolade in the world, transcending Western confines and celebrating the richness of global intellect.

Dr Young Sop Ahn, a political economist and information scientist with PhDs from MIT and Seoul National University, has taught and carried out research at esteemed institutions in South Korea and the United States, including MIT and Harvard