Indonesia’s next president will uphold Jokowi’s legacy. But that on its own might not be enough

- Whoever wins the election, fresh thinking and brave action will be needed to meet the developmental challenges facing Southeast Asia’s largest economy

- Whether the next government can set the right trajectory for Indonesia to become an advanced and prosperous nation by 2045 remains open to scrutiny

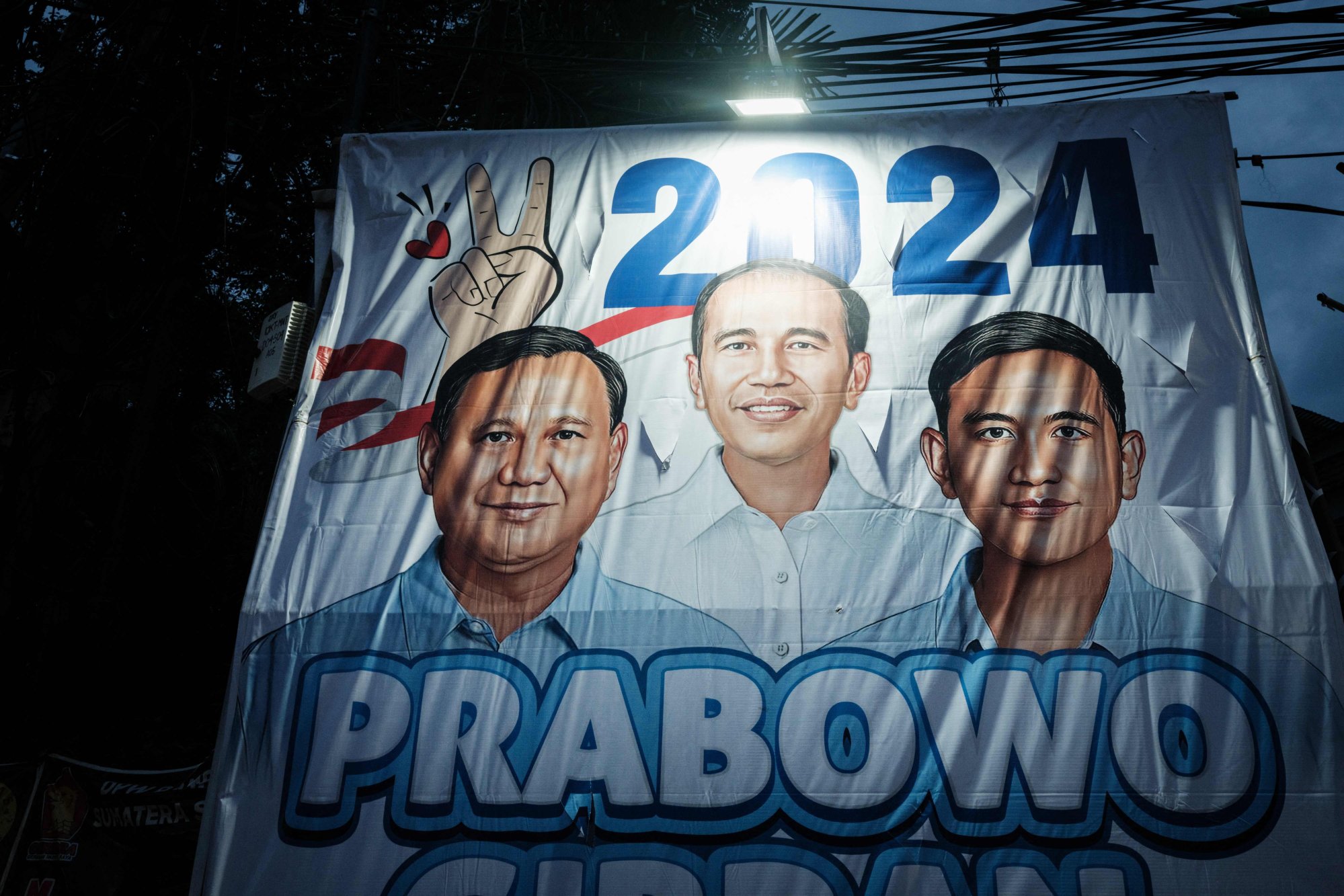

From a national development perspective, the three pairs of candidates – Anies Baswedan and Muhaimin Iskandar (Team AMIN), Prabowo Subianto and Gibran Rakabuming Raka, and Ganjar Pranowo and Mahfud MD – each have ways they can shape the future of Indonesia. So what are the policy possibilities post-election? And what are the potential effects on Indonesia’s development trajectory?

As policy (content) cannot be separated from the politics (process) and polity (culture), it’s important to start answering these questions by examining what the presidential nominees’ campaigns reveal about the state of the Indonesian political elite.

These agendas are reflected in the candidates’ campaign narratives: Team AMIN offer “change”, Prabowo-Gibran “continuity”, and Ganjar-Mahfud “improvement” – keywords that also capture their main policy approaches for key development issues.

Despite their promise to bring about significant change, Team AMIN have set quite a conservative target for annual economic growth of between 5.5 to 6.5 per cent until 2029. They say they aim to reach this through shared prosperity, wealth distribution, and social justice.

Jokowi under renewed fire for saying presidents ‘can take sides’ in election

Prabowo-Gibran’s target is 6 to 7 per cent using a vague, jargonistic strategy of “Jokowinomics”. This has been interpreted as a version of a “Pancasila economy” – basically a controlled market economy acting as a counterbalance against neoclassical economic tenets such as individualism and free-market economics.

Ganjar-Mahfud, meanwhile, have set an ambitious 7 per cent growth target with their “we have all” (semua ada di kita) strategy.

The three teams’ policy platforms share some similarities, as can be seen from their mission documents and campaigns. All three aim to accelerate economic growth to improve living standards and reduce poverty; recognise the importance of strengthening the country’s industrial base to reduce reliance on imports and strengthen export competitiveness; and agree that physical infrastructure needs to be improved to support economic activity and facilitate trade and investment.

However, they also differ in a number of ways. First, on the role of government, Team AMIN advocates limited government and greater reliance on private-sector initiatives. This is likely due to the influence of their campaign adviser, former trade minister Tom Lembong, who also headed Indonesia’s national investment agency. This contrasts with Prabowo-Gibran, who favour a more active state role in directing economic policy despite big businesses’ support. Ganjar-Mahfud take the middle ground: their policy platform envisages the government as the regulator and facilitator in guiding development, not an active player.

Second, on trade and liberalisation, Prabowo-Gibran’s focus on protectionism contrasts with Team AMIN’s emphasis on liberalisation and market-based solutions. Again taking the middle stance, Ganjar-Mahfud seek to balance the protection of domestic industries with fostering foreign direct investment-based innovation.

On social equity and environmental sustainability, Team AMIN and Ganjar-Mahfud emphasise tackling social inequality and environmental concerns, while Prabowo-Gibran’s primary focus is on growth and national self-sufficiency.

Investors are waiting to see if Jokowi’s signature policies – hilirisasi (downstreaming), the proposed shift of Indonesia’s capital to Nusantara in East Kalimantan, and infrastructural development among them – will continue.

The answer is clearly yes. These signature policies can be grouped into three broad types, the first of which is infrastructure such as ports, roads, and industrial complexes for connectivity in particular. All the candidates recognise that infrastructural development is crucial and have pledged to continue upholding this policy.

Whoever wins, what is clear is that Indonesia must be prepared to embrace different, creative policy priorities for development

The second is social protection, particularly social assistance, which Jokowi has emphasised. All candidates understand that this is a populist vote-winner that they must maintain, even if they differ on how it is delivered.

Third, all candidates will continue downstreaming as they know how important it is for Indonesia to move up the value chain. This is not limited to the mining/extractive sectors but extends to agriculture, fisheries, and even digital downstreaming. Team AMIN and Ganjar-Mahfud have declared that they will not stop at this but work towards “re-industrialisation”.

On the planned relocation of the new capital city, Prabowo-Gibran and Ganjar-Mahfud say they will continue this part of Jokowi’s legacy.

Prabowo-Gibran strongly support Nusantara, echoing Jokowi’s rhetoric by emphasising the need to develop areas outside Java. Notwithstanding criticism from academia and civil society, they have pledged to uphold sustainability and environmental responsibility in the new capital’s construction.

Ganjar-Mahfud have stated that they will study the project further, expressing concern about its potential impact on the local environment and the livelihoods of affected communities. In their campaign, they have offered “corrective measures” for parts of the process that may have been neglected, such as considering the impact on indigenous groups and the mitigation of environmental problems.

Team AMIN have been the most critical and omitted any discussion of Nusantara from their vision and mission document. They question its feasibility and high cost, arguing that the government should focus on addressing other issues such as poverty and inequality. Still, even if they win the election – which is made less likely by Prabowo-Gibran’s high poll ratings – Team AMIN are unlikely to stop the project outright, even amid growing resistance to the move from the public and civil servants. At most, the relocation can be delayed, as the new capital’s status is already enshrined in national law.

Indonesia election: is Jokowi’s ‘partiality’ for Prabowo a double-edged sword?

Whoever wins, what is clear is that Indonesia must be prepared to embrace different, creative policy priorities for development. All things considered, the presidential candidates’ proposed policies are not far-reaching enough to address the multifaceted challenges awaiting Indonesia, especially as it has aspirations to reach an advanced stage of development. Excellent technocratic capacity and strong political support must sustain and surpass what Jokowi has achieved.