Indonesia’s hi-tech vision for Nusantara and economy draws scepticism, ‘Pandora’s box’ fears

- A row between parking attendants and officials over a cashless payment system underscores Indonesians’ concerns about digitalisation’s impact

- The physical ecosystem, laws and bureaucracy to support the country’s tech goals such as Nusantara are lacking, analysts say

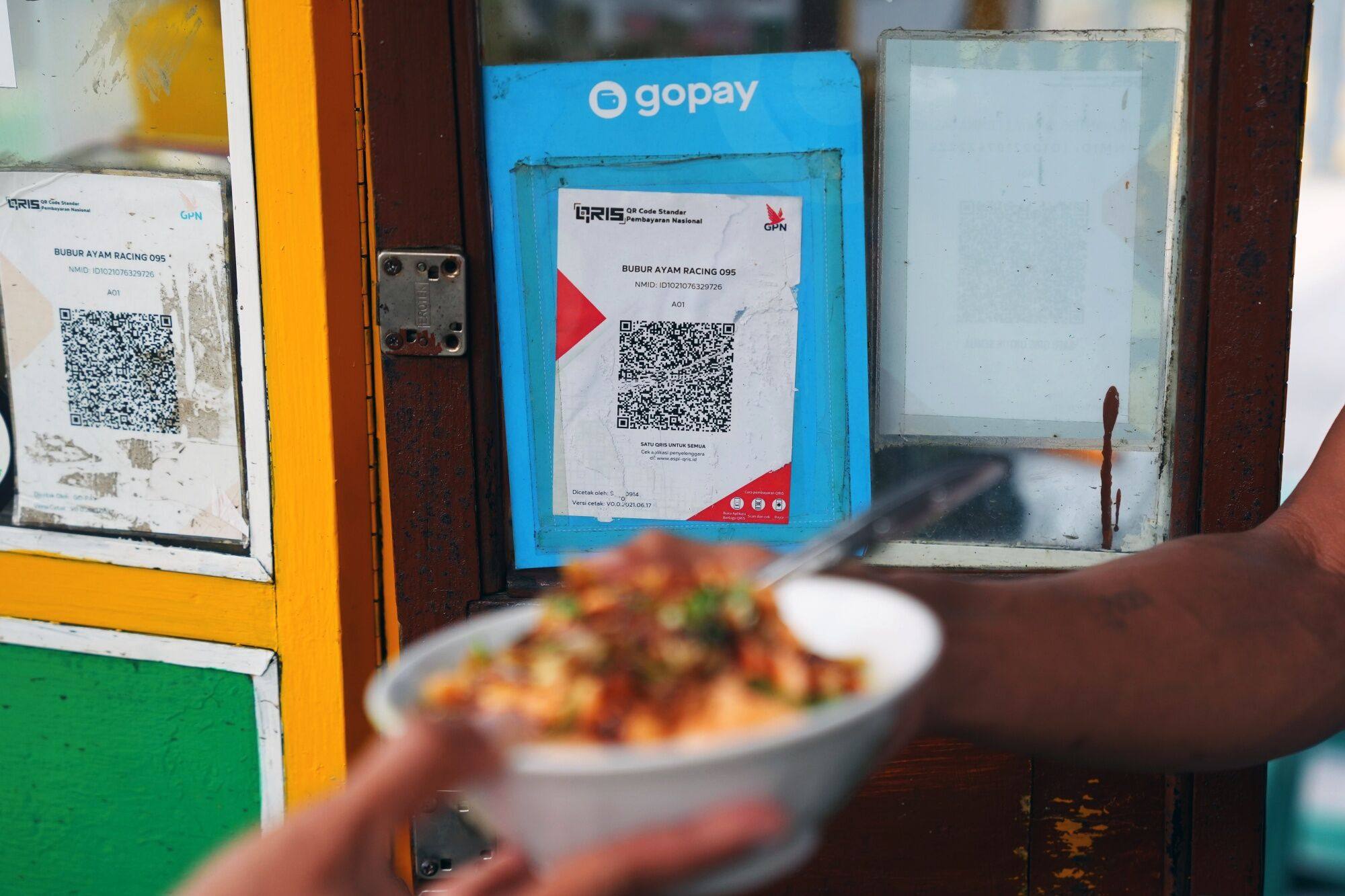

The parking attendants were concerned about their jobs after the municipal transport department proposed to allow drivers to use the country’s digital payment system to pay for parking fees.

“Down with QRIS! We refuse to work with it!” shouted one parking attendant angrily in the video.

The attendant was referring to the Quick Response Code Indonesian Standard (QRIS), a national app-based electronic payment platform recognised by most banks in Indonesia. Launched in 2020, the system can be used to pay for everything from public transport fees to restaurant bills and is endorsed by the government and the private sector.

Jokowi under renewed fire for saying presidents ‘can take sides’ in election

But for many Indonesians who are used to dealing with cash, using new technology evokes fear of invasive bureaucratic oversight and job loss.

Budi Rahardjo, the founder of PT Riset Kecerdasan Buatan, an Indonesian AI research company, said Indonesians needed to get used to digitalisation as it would have a major impact on every aspect of daily life.

“People should adopt it as it has the potential to affect efficiency in the way we do things,” he said.

Bali blast: families slam ‘secret deal’ in sentencing of Malaysian conspirators

Bold vision for Nusantara

Administrative and Bureaucratic Reform Minister Abdullah Azwar Anas said in a statement on January 23 that Nusantara will be home to an AI-anchored “digital government” by 2045.

“Our short-term goal is the relocation of civil servants to the new capital city and the gradual entrenchment of digitalisation in administrative affairs, to better prepare us for the eventual mode of smart governance,” he said.

Abdullah outlined five stages for the bureaucracy in Nusantara to become fully digital between now and 2045.

Budi said that while he welcomed the government’s bold vision, meticulous planning would be needed to establish such a futuristic capital city.

“Indonesia is not the first country to envision a smart AI-run city, and to date, no country has managed to realise one.”

When asked about potential job losses from technology, Budi said while some roles could become redundant, humans will always have a role to play in the workplace. “They can always be trained to do other things that machines can’t,” he added.

Other tech experts are less convinced about the government’s vision for a hi-tech Nusantara.

Sulfikar Amir, an associate professor of science, technology, and society at Nanyang Technological University (NTU), cited Indonesia’s budget constraints and a more decentralised system of government as significant challenges towards realising the goal.

“For a future capital city, the site Nusantara occupies is an unlikely location in the middle of a forest, which means enormous costs that would probably be several times more than the government’s estimate.”

‘People need entertainment’: Indonesia’s crackdown on porn sparks furore

In comparison, Xiongan had already received investments totalling US$57 billion as of September 2022.

Sulfikar said the physical ecosystem and bureaucracy to support Nusantara’s tech goals are lacking.

Weak legal framework

The notion that technology can be the panacea to transform Indonesia’s inefficient government system is naive, according to Sulfikar.

Indonesia walks ‘political’ tightrope with China over weapons trade with Manila

One major concern is whether Indonesia’s legal framework is robust enough to support its digitalisation efforts.

Without such a framework, Indonesia cannot protect the private data of its residents from misuse, Sulfikar said.

In July 2023, Teguh Aprianto, the founder of Ethical Hacker Indonesia, revealed that the personal data of 34 million Indonesian passport holders was traded on the dark web. In the same month, the personal details of more than 300 million Indonesian citizens were extracted from the country’s National ID Card database and put up for sale.

Even the supposed benefits that could be realised from digitalisation have come into question in certain sectors, such as education.

For instance, a study showed that 15 lecturers from public universities in Indonesia had reported poorer work performance and a decline in their well-being as a result of the introduction of a “digital-based audit culture”.

“The impersonal approach by technology here stultifies rather than liberates the creativity of lecturers as it forces them to work to satisfy academic performance points as set out by the apps,” according to the study by sociologists Oki Rahadianto Sutopo and Gregorius Ragil W at Yogyakarta’s Gadjah Mada University.

“Lofty visions are fine, but Indonesia must get its old house in order first before moving into a new one.”