Hong Kong’s ethnic minority jobseekers tripped up by lack of Cantonese end up doing low-skilled work, survey shows

- Most surveyed say it’s hard to break out of jobs as deliverymen, security guards and construction workers

- Hongkonger of Pakistani origin says learning Cantonese helped her land a job as a teaching assistant

After 10 years as a stay-at-home mum caring for three children in Hong Kong, Nazia Mehmood wanted to return to the workforce and teach English.

Born and raised in the city, the 40-something of Pakistani origin knew that her lack of proficiency in Cantonese would get in her way. Taking a course that helped her brush up on the language spoken by more than nine in 10 people in the city proved a big help in landing a job.

Jobseekers from Hong Kong’s ethnic minority communities stumble over the language barrier when looking for work. As a result, many end up doing low-skilled, manual work, according to official data and a recent study.

A lot of the time when they face discrimination, it is due to the language barrier

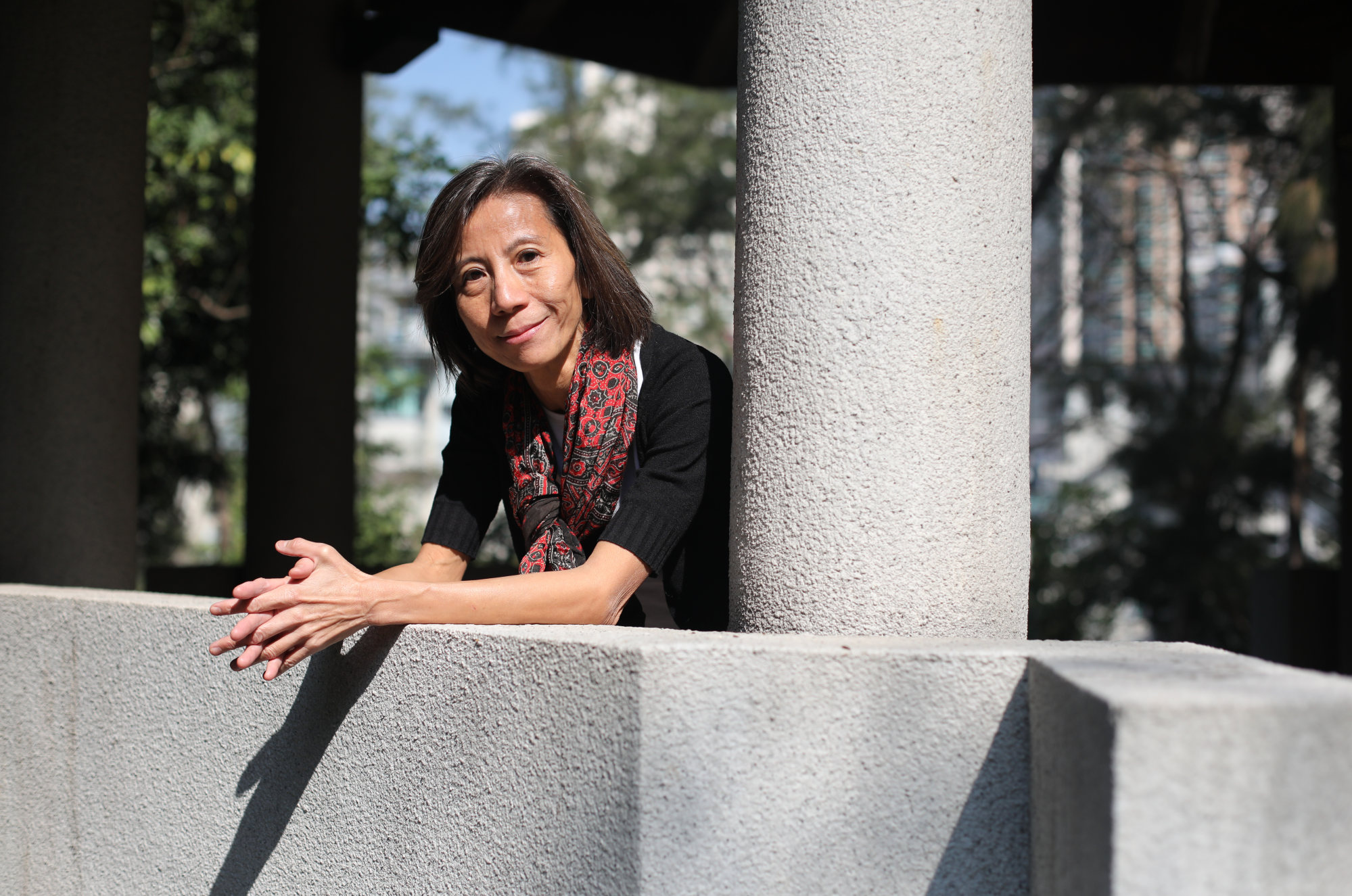

A survey on the employability of people from ethnic minority communities by Lingnan University professor of cultural studies Lisa Leung Yuk-ming showed that most found it hard to break out of working class jobs as deliverymen, security guards and construction workers.

Stereotypes of ethnic minority communities also persisted in the workplace despite Hong Kong’s claim to be inclusive and diverse, she said.

The survey done last year involved about 600 ethnic minority individuals aged mainly between 18 and 44, who were asked about the difficulties they faced in finding jobs and how they sought help from employment support services.

“A lot of the time when they face discrimination, it is due to the language barrier,” she said.

Even qualified individuals with degrees struggled to get a job if they could not speak Cantonese, she added.

According to the 2021 census report, there were 444,280 employees of ethnic minority backgrounds, including Caucasians, South Asians and Southeast Asians.

Almost 72 per cent of them were in “elementary occupations” such as domestic helpers, cleaners, food preparation assistants, messengers and deliverymen.

Most in this group were South and Southeast Asians, including Filipino and Indonesian domestic workers. Slightly over a fifth were Caucasians, people of mixed race, Japanese and Koreans.

Leung said there was an “entrenched impression” that people from ethnic minority communities were only capable of working in certain fields, and that meant fewer opportunities for job interviews in other professions.

“Stereotypes sometimes are hard to explain,” she said.

A Pakistani survey respondent told her they could not get teaching jobs in Hong Kong despite having a Chinese-language certificate from Beijing, as prospective employers doubted their language ability purely because of their ethnic background.

Although the Labour Department set up the Racial Diversity Employment Programme in 2020 to provide job-matching help through two NGOs, not many knew about the service, Leung said.

The plight of Hong Kong’s ethnic minority families seeking elderly care

The department told the Post that 882 jobseekers had gone through the programme since its launch, half of them of Pakistani and Indian descent. As of last December, 518 had found jobs.

Some of the frustrations which turned up among the survey respondents were familiar to Mehmood, the housewife who wanted to get a job.

She had spent a few years teaching English to her neighbours’ children and hoped to be more than a home tutor.

“Nobody knew about my talent and how I wanted to explore it with children,” Mehmood said. “That’s why I thought I should take some courses.”

She signed up for a five-month foundation certificate course funded by the charity Oxfam to undergo training in Cantonese language and early education.

It helped her to get her foot in the door as a teaching assistant, as she had an opportunity to do a practicum at a local kindergarten. The language training helped at job interviews later, when principals asked her to demonstrate her fluency in Cantonese.

Hong Kong ethnic minority pupils with special needs face delayed diagnoses, stigma

Now an English-language teaching assistant at a local kindergarten, Mehmood is already dreaming new dreams.

Recalling her school days, when she struggled with Chinese language and there was little support available, she said she hoped to show children from minority backgrounds that they could master the language and improve their options in life.

“I would love to teach Chinese to ethnic minority students,” she said.

One employer who appreciates having ethnic minority employees is Jojo Chong, principal of Western Pacific Kindergarten.

The school, which has been taking in ethnic minority students for the past 30 years, said although job candidates with South Asian backgrounds did not speak Chinese very well, she appreciated their bilingual ability.

She had four teachers who could speak Hindi, Urdu or Punjabi and they made up two-fifths of the employees.

“Our teachers with diverse ethnic backgrounds are a great help in communicating with parents who do not speak English,” she said. “The parents feel a strong sense of belonging to the school because the native language breaks down barriers.”