Did Chinese explorers from the Ming dynasty travel to the Americas decades before Columbus?

- A book on Chinese history has posited that the Ming dynasty’s Treasure Fleet journeyed as far as the Americas

- Author Sheng-Wei Wang has analysed the ancient Kunyu Wanguo Quantu world map from 1602 to back up her claims

This is the first in a two-part series on the voyages of the Chinese in the pre-Columbian era. Here, Victoria Bela examines the proposition that ancient mariners from the East had set foot upon the shores of America.

A massive Chinese fleet journeyed around the Indian Ocean during the early 15th century, undertaking seven meticulously planned voyages that took them as far as the east coast of Africa.

That is the question author Sheng-Wei Wang sought to answer in her book, Chinese Global Exploration in the Pre-Columbian Era: Evidence from an Ancient World Map, published last year.

“The mustering of resources and logistical planning was truly astounding,” said J Travis Schutz, a history professor at the California State University Los Angeles, who is not affiliated with the book.

After the emperor who sponsored the first six voyages died, the new emperor decided the seventh voyage would be the last.

At the end of the voyages, many of the ships, equipment and records, such as maps, were destroyed by the Ming administration, “resulting in the later Chinese losing geographical knowledge of the world”, Wang wrote.

How does the amazing world of underwater archaeology work?

One of those people was British submarine commander Gavin Menzies, who believed that the Chinese had reached the Americas in 1421. He wrote a controversial book on the subject in 2002, titled 1421: The Year China Discovered the World, which historians have rejected as “pseudohistory”.

However in her book, while analysing a major world map published a quarter of a century earlier than He’s charts, Wang leads the reader through a reimagined history of Chinese exploration that suggests they made it much further than the scholarly consensus.

“Even the most rigorous scholars admit the existence of a very puzzling phenomenon on the ancient Western maps: many supposedly ‘unknown’ areas were already mapped out before the Age of Discovery,” she wrote in the introduction of the book.

Wang began to wonder if someone else had beaten the Europeans to these locations – and if lost source maps could explain their origins.

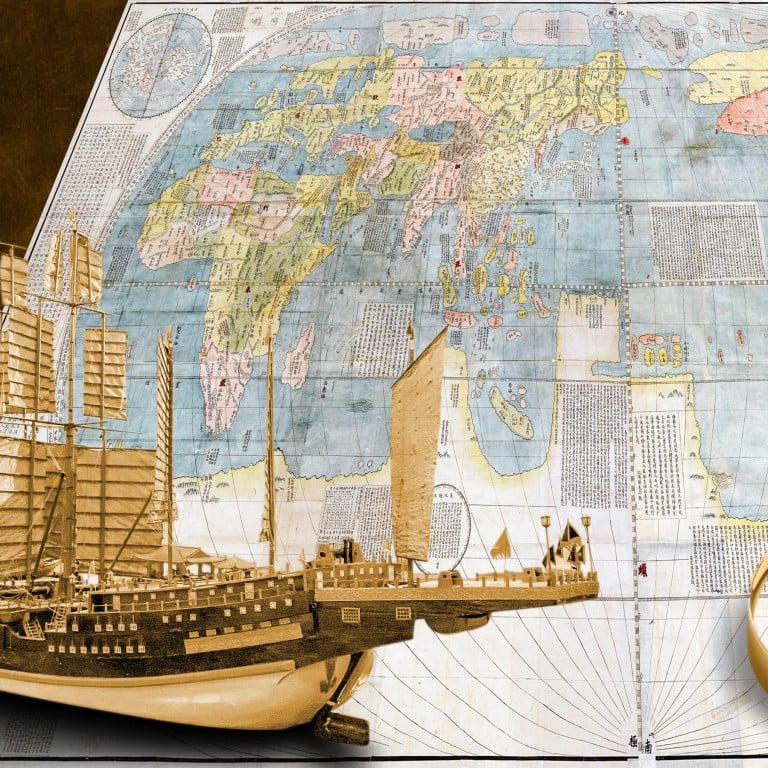

But it was a Chinese-language map published by Italian priest Matteo Ricci in 1602 while he was living in China, called the Kunyu Wanguo Quantu (KWQ), that saw the pieces of the historical puzzle begin to fall into place for Wang.

“[The KWQ is] the first world map all written in Chinese,” Wang said.

Rare 6-sheep chariot unearthed near mausoleum of China’s first emperor

But after comparing the KWQ with European maps published throughout the 16th century, Wang came to the conclusion that it could not have been drawn from European source maps alone.

Her theory was that while many of the maps were probably destroyed after the voyages ended, it is possible a few survived and Ricci got his hands on them.

She proposed that Ricci edited the Chinese source maps and brought in some Western elements from the European maps he was familiar with in order to produce the KWQ.

Throughout the book, Wang compared the KWQ to four major European maps from the 16th century. Along with her analysis, she also presented archaeological evidence discovered by people she came into contact with after she began examining the KWQ.

In the first chapter, Wang discussed Cape Breton Island in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia.

She originally began studying this area when she noticed the KWQ depicted a canal on the island that split it into two – a canal that was not present on the European maps.

And indeed, a canal did exist in the village of St Peter’s on the island.

Breakthroughs at archaeological sites offer window into early Chinese civilisation

Wang came into contact with architect Paul Chiasson and surveyor T.C. Bell, who had both discovered ruins “with Chinese characteristics” in the area. These ruins could not be explained by the local indigenous people, who did not claim them as their own.

Chiasson believed that the ancient canal, which was later rebuilt by the Canadian government, had in fact been built by Chinese explorers.

Wang added that although it may have been the Ming mariners who built the canal, it was possible that Chinese explorers from an even earlier time could have built it.

Looking for further evidence that this had been done by Chinese explorers, Wang asked Bell to look through the photos of his discoveries for evidence of black residue on the cut rock.

In ancient times, Wang said, the Chinese would use a chemical to help crack the stones, which would leave a black residue.

Bell ended up finding an image where this residue was present.

The evidence obtained at the island and the accurate depiction of the canal on the KWQ led Wang to conclude that Chinese explorers had in fact reached the island by 1433.

In more recent times, many scholars have come to believe that the Vikings also made it across the Atlantic Ocean to the Americas prior to the European explorers arriving.

How Xi’s nod to ancient Chinese ruins reinforces Beijing’s historical narrative

Bell actually found two Viking stone grave markers on the island. “The first and only located to date in North America,” Wang wrote.

But the markers were found on the bottom of a “Chinese road”, which Wang said she believed predated the Vikings – potential evidence of Chinese exploration in the area before 1000AD. This claim is contrary to what government archaeologists in Canada who examined the markers have concluded.

Wang continued the analysis of the American continents depicted in the KWQ in the book’s final chapter. When the map was published, “a vast area of North America had not been reached yet by Europeans”, Wang wrote.

Despite this, there were annotations present on the maps that suggested someone had in fact been there.

The KWQ had 17 annotations on the Americas describing aspects of the land such as the natural environment, geography, living conditions, flora and fauna. Only one of these was found on the European maps Wang analysed.

The KWQ also showed the Mississippi River, which the other maps did not.

The KWQ did not depict the Great Lakes, which Wang believed the mariners reached during their last voyage in the 1430s, but she thought the KWQ’s depiction was derived from maps drawn during the sixth voyage in the 1420s.

While there is a lot of work out there that re-examines ancient history, Wang said the focus was often on quantity over quality.

The terracotta army just added 20 soldiers, half a century after first discovery

When it came to maps, she said: “Most cartographers are emphasising only the geographical aspects of a map, but I think the map actually can give much more information [than] just the geography.”

The first and primary thing a map depicted was location, she said. The second is time, which can be deciphered by the existence of borders, countries and place names. The third aspect is historical events.

And the fourth are the characteristics of a location depicted through annotations of the geography, animals, plants and people present. Throughout her research, Wang examined the KWQ with these four aspects in mind.