Did Chinese explorers land on Australia’s shores almost 200 years before Europeans?

- Research of 1602 map, the Kunyu Wanguo Quantu, has raised questions about the history of Chinese exploration

- A book on the subject claims that the Ming dynasty Treasure Fleet may have journeyed to both Australia and New Zealand

While Chinese marine voyages in the early 15th century are known to have been massive undertakings, most scholars believe these journeys only took the explorers to countries bordering the Indian Ocean.

That is what author Sheng-Wei Wang has investigated in her book, Chinese Global Exploration in the Pre-Columbian Era: Evidence from an Ancient World Map, published last year.

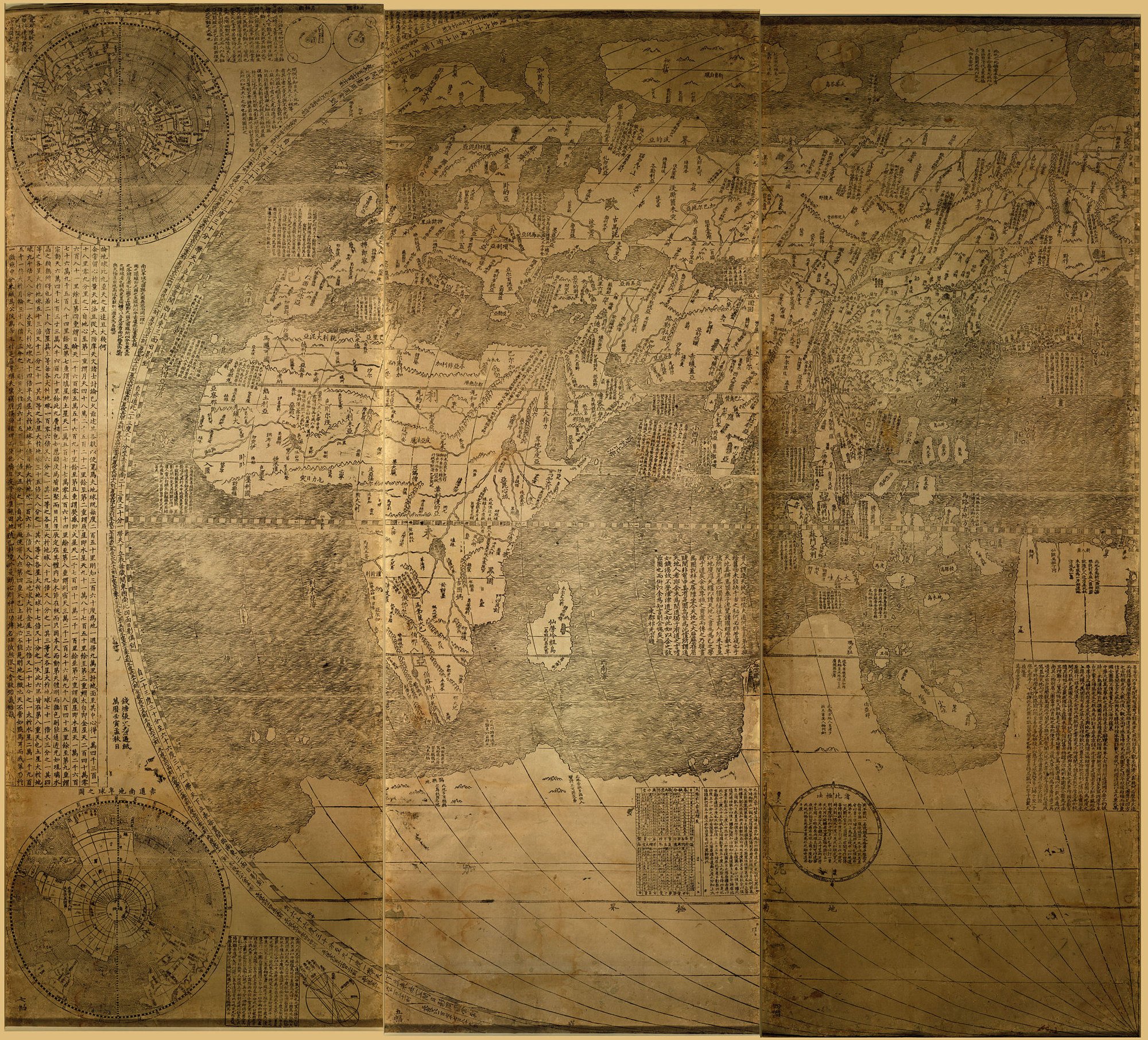

Wang’s conclusions are based on her analysis of the first Chinese-language world map, the Kunyu Wanguo Quantu (KWQ), which was published in 1602 by Italian priest Matteo Ricci while he lived in China.

“Although the extent of his expeditions is still under debate, most scholars agree that his mariners reached Africa during their fifth to seventh voyages,” Wang wrote.

Wang’s analysis led her to conclude that Chinese explorers had reached the Americas before Christopher Columbus.

Academic explains China child slavery trap created by 17th century farming style

But how would the Chinese mariners have reached the American continent?

By rounding the southern tip of Africa, Wang told the Post. Once you round the continent, “currents will bring you to America”.

While this theory is not supported by most historians, there are others who have come to similar conclusions in the past, such as British submarine commander Gavin Menzies who in 2002 published the book, 1421: The Year China Discovered the World, in which he wrote that the Chinese had reached the Americas in 1421.

This path during the seventh journey brought their ships to Canada, but Wang said it was likely that they also sailed this way during the sixth voyage, which brought them to the Gulf of Mexico.

For Portuguese mariner Dias, rounding the southern tip of Africa led to the discovery that this route would give the Europeans sea access to Asia.

In the fourth chapter of the book, Wang dated the African portion of the KWQ to 1433, based on political information such as country names and territories present on the map.

With this dating, an interesting feature of the map became apparent.

Before the Europeans sailed around the southern tip of Africa, they believed that the southernmost end of the continent was the Cape of Good Hope. Their maps continued to depict this in the 16th century.

However, the southernmost tip of Africa is actually Cape Agulhas. The KWQ depicts this correctly – despite this portion of the map being dated by Wang to 1433. Wang therefore determined that Ricci must have drawn this part of the KWQ using Chinese source maps.

This is further supported by the fact that parts of Africa’s internal landscape appear on the KWQ, such as Lake Victoria and mountains in the sub-Saharan region. These were depicted “close to reality”, Wang wrote.

Meanwhile, 16th century European maps had limited geographical annotations about the interior of sub-Saharan Africa; 11 annotations that were on the KWQ were completely absent from these maps.

But according to Wang’s book, the extent of Chinese exploration did not end in the Americas.

There is another part of the world that the Ming mariners could have reached around 200 years before Europeans – Oceania.

It was this depiction of a large connected continent taking up the entire bottom section of the map that puzzled Wang.

Although Europeans liked to illustrate the unexplored land in the south this way, Chinese cartographers had never done so.

However, when Wang began to examine the KWQ more closely, she began to see evidence of a “Chinese origin”.

The first was that the actual outline of northern Australia appeared to be somewhat reflected in the stretched out coastline of the large continental mass.

The first documented landing of Europeans in Australia was by Dutch explorers in 1606, which was after the KWQ was published.

And yet Wang found annotations on the KWQ that had mountains and bird names that lined up with the geography of Australia.

The Europeans also “did not know the existence of New Zealand in the 16th century”, only landing on the islands in the mid-17th century, she wrote.

If the Europeans had not reached this land yet, and their maps did not show it accurately, what source could Ricci have referred to to create the KWQ?

Wang suggested that he used maps created by the Chinese mariners around their fifth voyage.

The KWQ provides evidence that by the 1420s, Chinese mariners had explored Australia, New Zealand and even Antarctica, long before European explorers, Wang wrote.

She also said she believed that, while Ricci referred to Chinese source maps to help annotate Oceania, he still used the European concept of a large southern continent while creating the map.

To provide further evidence for Chinese exploration of New Zealand in the early 15th century, Wang included the findings of British surveyor T.C. Bell within her analysis.

In the early-2000s, due to landscape changes brought about by a tsunami, Bell discovered what appeared to be two crushed ships embedded upside down in a hill on New Zealand’s South Island.

In them, he found signs of a “Chinese imprint” – pieces of concrete used to strengthen the ships were glued together using sticky rice adhesive, which was a powerful glue that was also used in parts of the Great Wall, Wang said.

She said this rice adhesive was tested and confirmed in a lab. Bell also found evidence of Chinese lettering imprinted into the concrete.

This evidence is “direct [hard] evidence of Chinese junks and Chinese presence in New Zealand”, Wang wrote.

As to why the ships had come to be buried within a hill in the first place, Wang said a meteorite was believed to have crashed in the Tasman Sea around this time. It may have occurred during the seventh voyage, affecting some of the fleet that were in the area at the time.

Bell found even more evidence like art, house foundations and city gateways that suggested the Chinese could have reached New Zealand even earlier than the Ming voyages – perhaps 4,000 years ago.

But why might the Chinese mariners have tried to round Africa in the first place? Wang said it have been to bypass taxes.

Chinese ships travelling from the Indian Ocean had to pass through the Red Sea canal, sailing above Africa to enter Europe. While it made sense for trading ships to pay the taxes, it made less sense for explorers to do so.

In fact, a massive number of vessels like the Treasure Fleet would probably not have been able to pass through these seasonal canals that were “not suitable for ocean-going ships”, Wang wrote.

If Wang’s analysis of the map and the true reach of Zheng He’s voyages is true, how could this have been lost from history?

After the seventh and final voyage, China decided to “withdraw completely from the world stage”. This included banning voyages and imposing a “sea ban”, burning the Treasure Fleet and destroying equipment like maps, Wang wrote.

Even after the ban was partially lifted in the mid-16th century, no large Chinese ships built for exploration were sent out around the world.

Wang said that the Chinese source maps that Ricci possibly used to draw the KWQ may have been lost because, at the time, the Chinese did not “treasure their maps”.

But evidence of these lost maps may be reflected in the KWQ, depicting a lost account of Chinese exploration that suggests that these voyages – which are already known to be “unmatched” in history – could have had an even larger reach than previously thought.