Chinese archeologists have dug up fresh clues about early humans – and stunning new insights

- Researchers in southwestern China uncover dramatic new evidence about paleolithic people, turning back the clock on a key moment in prehistory

- Insights about diet, abilities and beliefs could ‘upend’ our understanding about how Old Stone Age people lived

As the waters began to recede from a flash flood on a river in southwestern China in 2021, few could have predicted how such a rare weather event would illuminate the region’s distant past – and the lives of some of its earliest palaeolithic human inhabitants.

The Mengxi River site in Sichuan province has since revealed clues about how people lived 50,000 to 70,000 years ago, a key moment in the study of the origin and spread of modern humans.

It seems the ancient riverside hunting settlement was a thriving hive of activity. Scientists have unearthed a trove of tools, animal fossils and plant remains. But signs of ancient carvings and cuttings, as well as the use of fire point to the wisdom and specialisation of the site’s residents.

Discovery of ancient Chinese dam points to rise of ‘great power’ 5,000 years ago

“They lived by a small river, surrounded by ancient forests with towering trees, that were home to elephants, rhinos, deer and other animals,” Wang Youping, a professor of the School of Archaeology and Museology at Peking University, told local outlet Sichuan Online.

“Tens of thousands of years have gone by. Mighty trees fell, leaving behind countless branches and trunks, while animals turned into fragments of fossils,” he said.

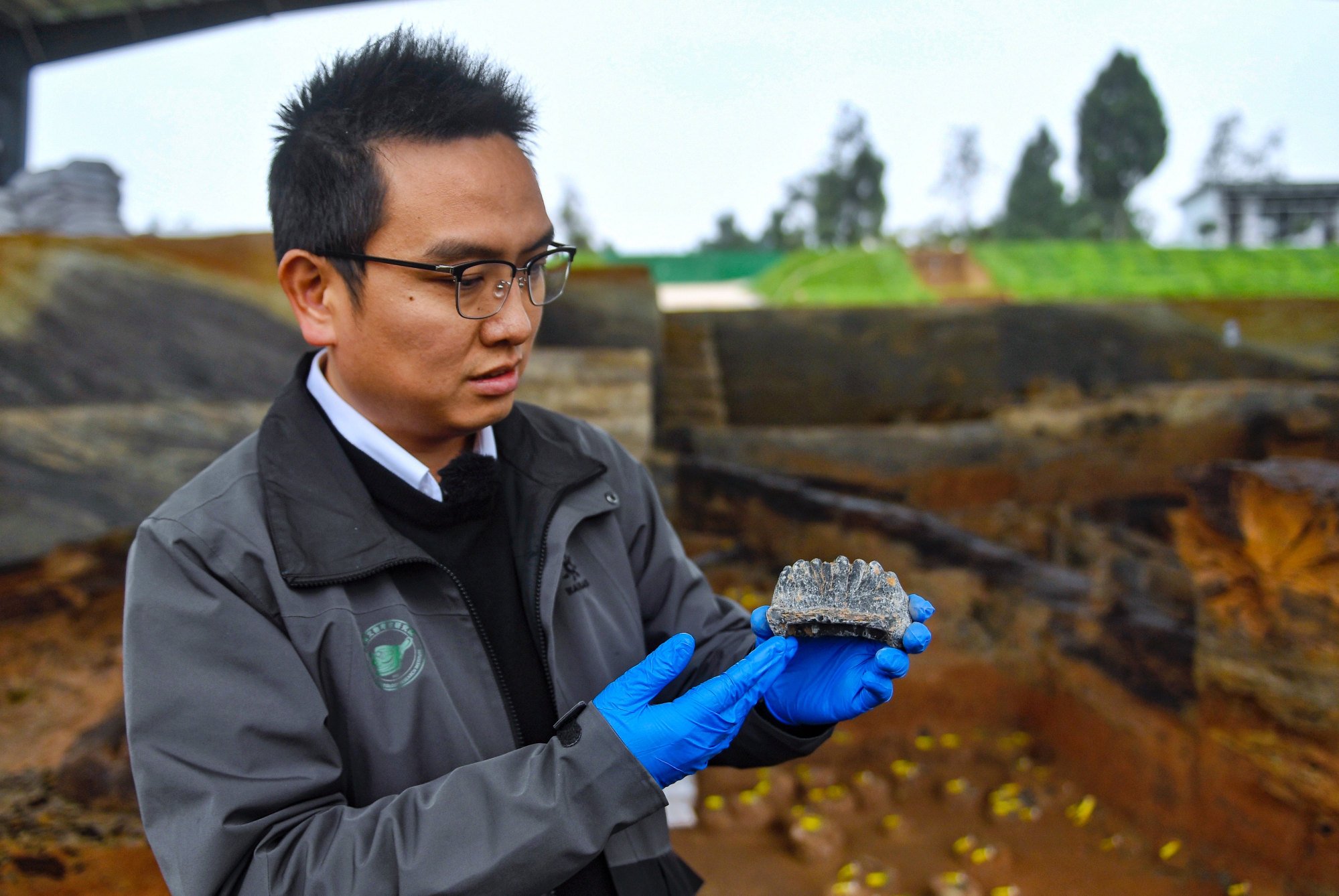

The site is rich in animal fossils and reveals a profound understanding of animal resources, as well as the hunting capabilities of the inhabitants, according to Zheng Zhexuan, leader of the archaeological team from the Sichuan Provincial Cultural Relics and Archaeology Research Institute.

Zheng said at least 30 species of animal fossils have been found, including elephants, rhinoceroses, bears, cattle, deer, macaques, fish, turtles, snakes, frogs, birds, porcupines and bamboo rats.

“They represent almost all large groups of animals, including different sizes, water, land and air animals, as well as carnivores and herbivores,” he said.

The Mengxi River site, he added, is the earliest site in China where abundant aquatic animal remains were uncovered and one of the earliest locations that reveals clear evidence of carnivores being processed and consumed.

Researchers found cutting marks on a bear’s toe bone, which could point to ancient humans breaking animal bones to eat the marrow inside.

The scientists said humans at the site were very good hunters because they were going after large carnivores such as bears – very dangerous even in modern times – and giant animals such as elephants and rhinos.

One piece of animal bone recovered from the site revealed more than 10 parallel lines scratched onto a surface area about 3.5mm (0.14 inches) wide, and “X”-shaped scratches on other bones, possibly pointing to symbolic behaviours exploring art or the spiritual world.

Plant remains were also rare finds for archaeologists. It is generally believed that palaeolithic people were hunter-gatherers, but the scarcity of plant remains has kept research limited in this area.

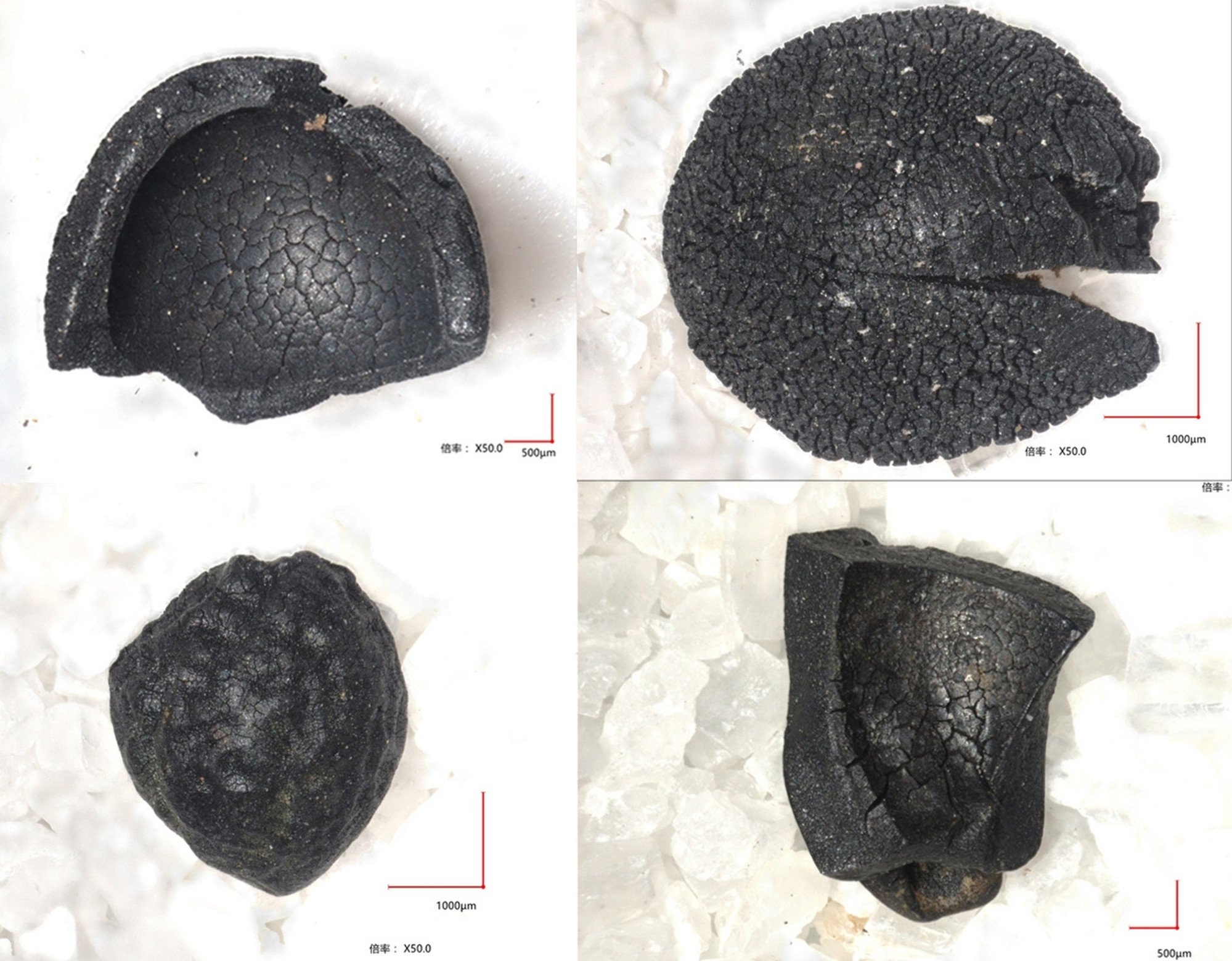

The team found seeds and fruits of mostly edible plants in the soil. Zheng said the specimens included fruit such as peaches and grapes, and nuts such as acorns and walnuts – the earliest evidence of nuts at any palaeolithic site.

Scientists also uncovered clues that suggested the early use of medicinal plants, such as a species of elderberry known as Chinese elder and the Ajuga ciliata Bunge, which are used in Chinese medicine to treat injuries, relax muscles and enhance blood circulation.

Scientists find first genetic evidence of multiracial population in ancient China

The widespread use of plants was previously thought to have begun during the transitional period from the Old to New Stone Age.

“But the discovery of a large number of plant remains at the site shows that ancient humans here had a profound knowledge and utilisation of plant resources, which will greatly rewrite the history of the use of plants by prehistoric humans,” he said.

“The rich animal and plant resources provide invaluable materials to understand the environment and climate at that time.”

People at the time mostly made tools from petrified wood – fossils of wood that have turned to stone – but they also fashioned the bones of large mammals into tools, the researchers said.

As for the use of fire, archaeologists discovered carbonised wood, burnt acorns and the jaw bones of a stegodon – an extinct type of elephant – that had been exposed to high heat, possibly through the use of fire.

“Many carved symbols were found there, some very finely done, providing us with precious materials for studying non-functional behaviours of ancient humans,” he told Sichuan Online.

“If unearthed fish bone fossils were used by humans, it means that they began to utilise aquatic resources tens of thousands of years ago, challenging the current belief that human use of fish only began 10,000 years ago.

“If acorns with traces of fire roasting were confirmed to be processed by humans, it would also upend our current understanding,” he said.