China builds world’s most detailed human genome with ‘enormous’ implications for disease treatment

- Experts hail milestone for potential benefits in precision medicine, especially among Han, the largest ethnic group in the world

- Advances could help answer the question of who Chinese people are at the genetic level

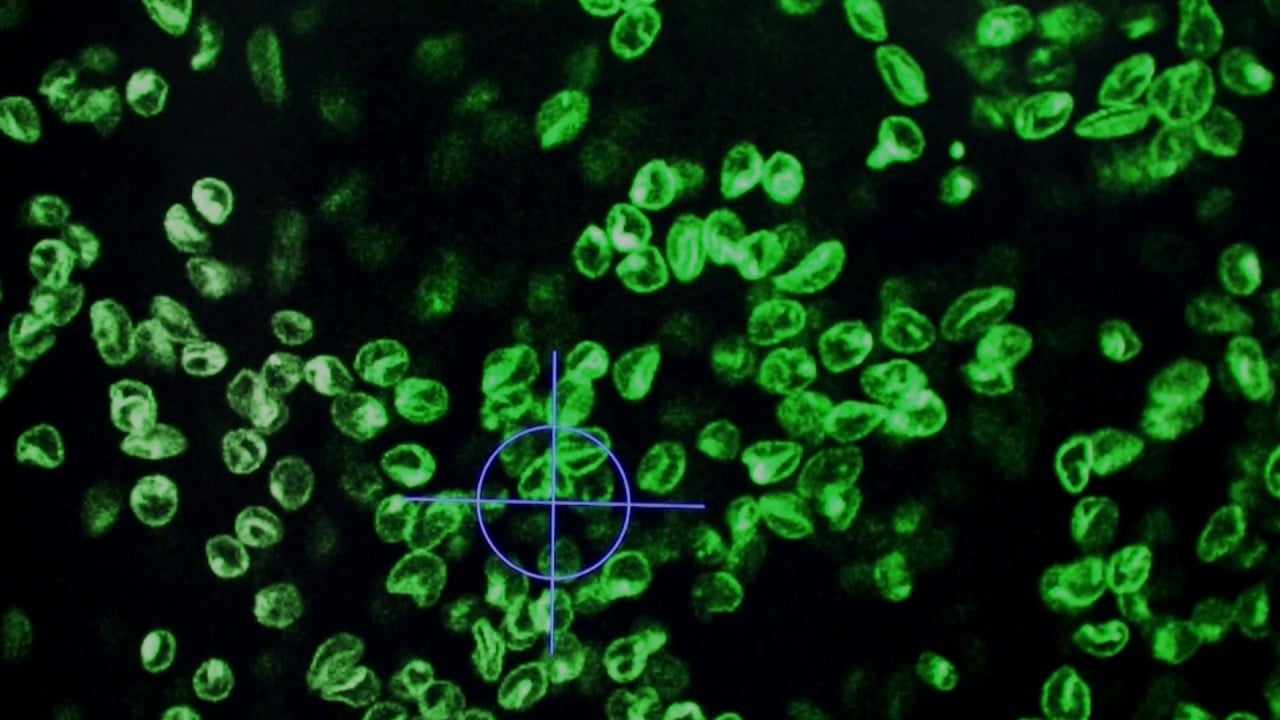

Chinese scientists have assembled the world’s most detailed human genome yet, a “landmark” event that could guide targeted drug discovery and medicine.

Research leader Gao Zhancheng said that until now sequencing-based diagnoses had been based on an incomplete reference genome from the United States, state-owned Science and Technology Daily reported on Thursday.

Gao, a director of respiratory and critical care medicine at Peking University People’s Hospital, said the US-based genome, which was used to judge “normality or variation”, was mostly derived from individuals of African and European ancestry.

Scientists find first genetic evidence of multiracial population in ancient China

The lack of representation of Asians in the genome can cause “large deviations” when diagnosing or treating patients, and could affect the development of targeted drugs, he said.

To address the gap, in 2020 Gao and his research team set out to construct a reference of the Chinese genome, particularly of the Han ethnicity, the largest ethnic group in the world.

The resulting genome was the “highest quality diploid [two complete sets] human genome”, assembled so far, the researchers said in a paper published in the journal Genomics, Proteomics & Bioinformatics in August.

The feat is a “landmark event in our country and even the world”, Zhang Xue, an academic from the Chinese Academy of Engineering, who was not an author of the paper, told Science and Technology Daily.

An ongoing international mission

Sequencing the human genome has been an international mission since the Human Genome Project was launched in 1990. In the early 2000s, the project generated the first sequence of the human genome.

In 2022, the Telomere-to-Telomere (T2T) consortium, a global community effort to assemble the human genome, presented a complete sequence of the human genome, called T2T-CHM13.

This assembled genome addressed the gaps left from the human genome first sequenced two decades earlier, and reached “its highest level of continuity and accuracy after 20 years of effort”, the paper said.

CHM13 is expected to replace the US-based reference genome, GRCh38, that is the standard in research and medicine.

However, while the assembly of T2T-CHM13 was “a remarkable scientific achievement”, it did not represent the genome of a “real human individual”, the paper said.

Hong Kong’s DNA pioneers launch blood tests to find cancer

That is because it originated from a “hydatidiform mole” – a non-viable fertilised egg with no maternal chromosomes, that instead has two sets of duplicated paternal chromosomes.

This also means that T2T-CHM13 is a “haploid genome”, containing only one set of chromosomes, with no Y chromosome.

But it is still considered a complete, gapless genome since it sequenced chromosomes from telomere to telomere – or tip to tip.

The Chinese team’s reference is a diploid genome, reflecting the actual human genome, containing both sets of chromosomes as well as the Y chromosome.

‘Highly qualified as a reference genome’

The villager who gave the blood sample lives near the ruins of the ancient capital built by Tang Yao, said to be one of China’s earliest emperors. So, the team called the reference genome T2T-YAO.

“The quality of T2T-YAO is much better than all currently available diploid assemblies,” the paper said, adding that even the haploid version of the genome was higher quality than T2T-CHM13.

“All the assessments of T2T-YAO ensure that it is highly qualified as a reference genome”, that is an accurate representation of a real human being, the team wrote.

The Y chromosome of this particular reference represented much of the Chinese population, excluding people in areas like Xinjiang and Tibet, Kang Yu, a researcher at the Chinese Academy of Science Beijing Institute of Genomics and co-lead of the research, told Science and Technology Daily.

Science journal will weigh in on whether Chinese team made genetic engineering breakthrough

After comparing T2T-YAO with T2T-CHM13, the researchers found that it had around 330 megabases of exclusive genetic sequences, 3,100 unique genes and tens of thousands of nucleotide variations.

By comparing the sequenced genetic data of patients with a reference genome “healthcare providers can tailor personalised treatments according to an individual’s genetic make-up and specific disease risks”, Zhang wrote.

This approach to medicine, also called precision medicine, was still a developing field, Zhang said, but “the potential benefits of precision medicine are enormous”.

Understanding ‘the Chinese people’

T2T-YAO could also help us better understand inherited and observable characteristics of disease, “especially within the context of the unique variations of the Chinese population”, the paper said.

Cheng Jing, an academic at the Chinese Academy of Engineering who was not an author of the paper, told Science and Technology Daily that the assembly of T2T-YAO could even help answer the question of who Chinese people were at the genetic level.

“Due to the limitations of sequencing technology, constructing high-quality T2T diploid genomes of a real individual remains challenging even after the completion of T2T-CHM13,” Zhang wrote.

While T2T-YAO took only two years to assemble, the previous most detailed genome was the result of three decades of work led by US-based scientists.

Chinese hospital detects new gene sequence for rare p blood type

Kang said the reason they were able to assemble this reference genome so quickly was because of “the rapid progress of DNA sequencing and splicing technology”.

He stressed that the previous efforts of scientists around the world made this human genome sequence possible.

Yu Jun, the former deputy director of the Beijing Institute of Genomics, who was not an author of the paper, said the next step was to promote the sequencing of other genomes, including those of different ethnic groups in China.

“Eventually we hope to launch a nationwide genome sequencing project,” Yu said.