In ‘big test’ for India, China and Bhutan push to solve border dispute and establish official ties

- Chinese and Bhutanese officials wrap up new round of border talks and agree to work towards formal diplomatic relations

- Analyst says thaw in ties is ‘severe strategic setback’ for New Delhi’s security efforts in Himalayas, where it faces boundary spat with Beijing

Wrapping up a new round of border talks in Beijing on Tuesday, the two countries signed a cooperation agreement on the responsibility and functions of a technical team for the delimitation and demarcation of the boundary.

China-India border talks: dispute to be resolved ‘as soon as possible’

Han described Bhutan and China as “friendly neighbours sharing mountains and rivers” and hailed the progress in bilateral ties in recent years, according to the official Xinhua news agency, which said both sides agreed to accelerate the demarcation process and the establishment of diplomatic relations.

Dorji was quoted by Xinhua as reiterating Bhutan’s support for the one-China principle.

“Both sides have firm determination and a sincere desire to demarcate their boundaries and establish diplomatic relations at an early date,” Dorji said, adding that Bhutan was willing to maintain the momentum of cooperation with China and push for the greater development of bilateral ties

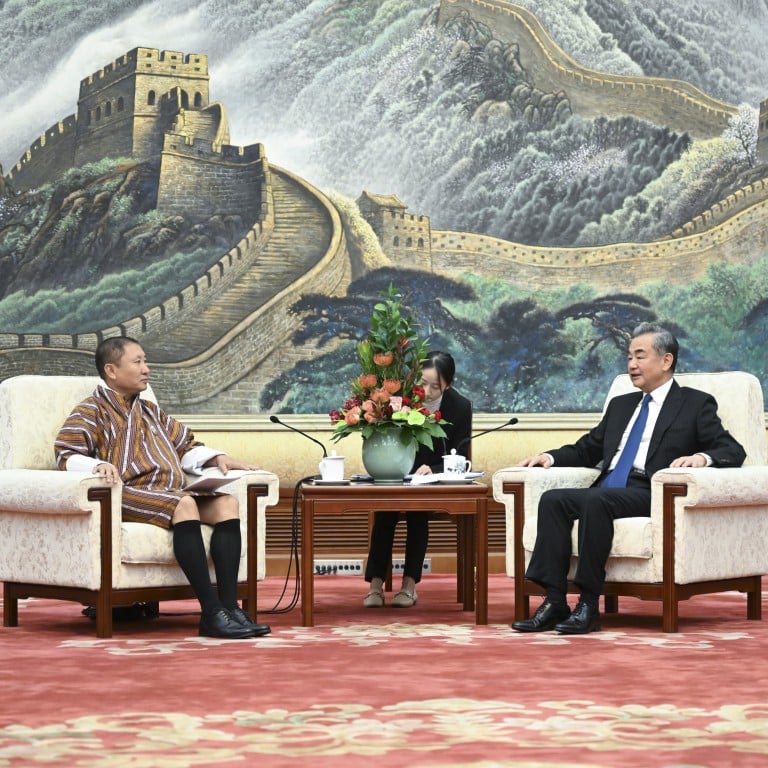

In a meeting with Dorji on Monday, Wang said China was ready to conclude boundary negotiations and establish diplomatic relations with Bhutan “as soon as possible”.

A border settlement and diplomatic ties with China “fully serves the long-term and fundamental interests of Bhutan”, said Wang, the top foreign policy aide to Chinese President Xi Jinping.

Zhao Gancheng, a researcher at the Shanghai Institutes for International Studies, said the agreement and remarks by both sides signalled a fresh consensus on the unresolved border issues, marking an important breakthrough.

Zhao said if China could establish ties with Bhutan, it would mark major progress for Beijing’s diplomacy in South Asia as the landlocked Himalayan nation’s foreign policy had been heavily influenced by India.

“It is very encouraging, but this breakthrough will no doubt pose a big test for India. It remains to be seen if and how New Delhi would respond. Will it intervene again like it used to do in the past?” he said.

Between 1984 and 2016, there were 24 rounds of border talks between China and Bhutan. Talks were suspended after the Doklam border crisis in the summer of 2017, when Chinese and Indian troops were locked in a 73-day face-off in the remote area where Bhutan, the Indian state of Sikkim and China’s Tibet autonomous region meet.

Doklam is of strategic importance because of its proximity to Siliguri Corridor, known as the Chicken’s Neck, which connects India’s northeastern states to the rest of the country.

Border negotiations picked up after the two sides signed a “three-step road map” for expediting talks in October 2021.

Wang Dehua, a regional affairs expert at the Shanghai Municipal Centre for International Studies, noted the current Bhutanese administration led by Prime Minister Lotay Tshering was considered Beijing-friendly, but India remained the biggest hurdle in China’s ties with Bhutan.

“This is a good opportunity for China and Bhutan to get the job [of establishing diplomatic ties] done. But that said, I doubt if it is possible for the Bhutanese government to make such a major foreign policy decision without seeking India’s support,” Wang said.

“There is probably a 50 per cent chance of success, depending mainly on whether India would give the green light. But remarks by Bhutanese officials [about seeking closer ties with China] have nonetheless posed a dilemma for New Delhi, which in turn could be leverage for China vis-à-vis India.”

China-India border talks raise hopes ahead of Xi, Modi Brics trip

In an interview with Belgian newspaper La Libre in March, Tshering said Bhutan did not have “major border problems” with China and expressed hope that the demarcation of territories could be completed within “one or two meetings”.

He also denied reports that China had built villages inside Bhutanese territory and said India, China, and Bhutan all had equal say in resolving the Doklam plateau dispute, raising concerns in New Delhi about Thimphu’s shifting stance.

Robert Barnett, founder and former director of Columbia University’s modern Tibetan studies programme, noted things seemed to be moving forward quickly as the Bhutanese government tries to clinch a border deal with China before its term runs out next month.

“So far I think we have not seen any serious indications that India is unhappy with Bhutan’s moves on this issue, and it seems unlikely that Bhutan would act without having support for its plans from India,” he said.

“But I think it’s clear that the Chinese side stands to gain from any flux or uncertainty in relations between India and the other Himalayan states. When China decided to resort to the exceptionally heavy pressure tactics it is using on Bhutan, it must have been aware that this could unsettle the existing alliances in the region, and perhaps that is its aim.”

Jagannath Panda, head of the Stockholm Centre for South Asian and Indo-Pacific Affairs at the Institute for Security and Development Policy in Sweden, said China’s efforts to draw Bhutan closer were clearly aimed at India.

He described the warming China-Bhutan ties as “a severe strategic setback” to India’s Himalayan security undertaking.

“China’s boundary negotiation strategy with Bhutan is not entirely a new episode. What is however striking is Beijing’s continuous persuasion to have a boundary deal with Bhutan overlooking India’s concern while complicating the existing boundary dispute with India. This certainly complicates the Himalayan valley security environment,” he said.